Baby Kicks

Yam suddenly sprung forward from her relaxed posture on the couch and held her hand over her stomach. “Come quick!” She exclaimed. I rushed over and she grabbed my hand and placed it where hers had been. Her hand over mind, and ours over the mystery, we became still and silent with anticipation. At first nothing, but then everything!

The little “kick” of our son in the womb suddenly made the pregnancy real for me. The whole experience had been very real for Yam from the beginning. The morning sickness, the strange appetite, the bodily changes. All her sensible experiences had already been changing for months. These changes gave her an intimate experience of reality long before I even began to get a true sense of it.

Awareness of the distinction between theoretical knowledge of a reality and the actual experience of it is vital in the life of the Orthodox Christian. Knowing God the Father loves us is one kind of knowledge. Knowing the love of the Father personally—coming to the awareness of every good and perfect gift that comes from Him and being capable of receiving them like a child—is of another and better knowledge. It is the knowledge of acquaintance versus the knowledge of sonship.

Michael Garten has been doing some remarkable research and apologetic work concerning icon veneration. In a recent video he made a very insightful point that was both encouraging to me personally, and something I’ve tried to emphasize in my own various conversations with people about iconography and how to engage it well:

Iconography is three-dimensional.

This point may come as a surprise to most people. Anyone who has seen an icon would probably not include the adjective “three-dimensional” as a defining characteristic of the art. Yet it’s true. In fact, the three-dimensionality of the icon is one of the most practically important features.

The third dimension of the icon is like the experience of a father feeling their child kicking in the womb of the mother. It is the movement of one reality into the reality of another. Two realities begin to merge as one reality, and this is occurring both on a cosmological level as well as the level of personal experience.

An Appalachian Iconographer

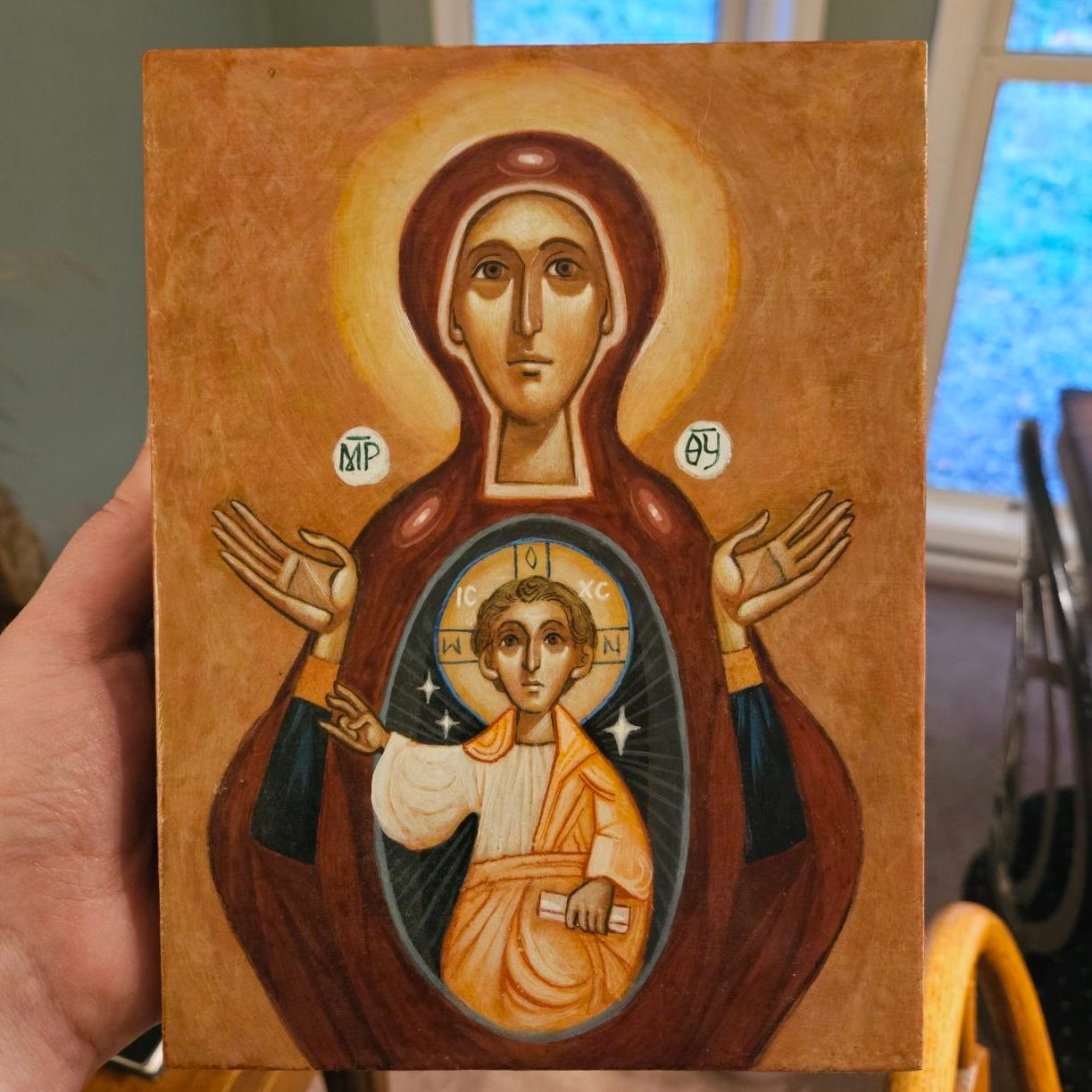

Yam asked me to paint an icon of Our Lady of the Sign as her gift celebrating our 10th anniversary. In much of my recent work I’ve been painting familiar subjects in an immediate or direct fashion, and this is the approach I used for this icon as well. This means starting without any sketches or models to imitate. One of the benefits of this approach is that I am forced to test and more deeply internalize the central images of the Orthodox Christian faith.

The icons painted in this approach often inherit a more folk appearance. I imagine this is some amalgam of my iconographic and other artistic influences, along with my cultural connection to Southern American folk art as Western North Carolina native. Although there may be those who find some sort of fault in this, I would strongly suggest they are very misguided.

I’ll dedicate more time to this in a paid-subscriber post at a later date (this is your cue to become a Founding Member or pick up a yearly subscription!).

For now, just know that iconography should always be indigenous even when the ancient models are being followed. It is proper for Orthodox Christianity to develop in a culture organically, which will both import something of another culture while also converting the local culture. Managing to get an Appalachian to larp as a Greek, Russian, Antiochian, or any other ethnic group is not the same as converting an Appalachian to Orthodox Christianity. I digress.

The point is that it’s very desirous for my work to visually express the Orthodox faith with both a traditional and local dialects. This is one small mode of loving my literal neighbor as an iconographer. With enough time and resources, I hope to be able to provide every parishioner with their own icon of the “Appalachian School”. In the meantime, I do what I can by the mercies of God.

Our Lady of the Sign

Iconographic Type

It’s helpful to think of icons in thematic and typological categories. This is because there can be several variations of one type of icon. These variations draw attention to specific theological emphases within the overarching type, and yet without eclipsing the other theological emphases present.

In this example, Our Lady of the Sign, fits within the “Mother of God Orans” icon type.

Orans refers to the posture of the hands. The uplifted, palms-out posture indicates the elevation of the heart (nous) to God in prayer. We should note, however, that the orans gesture itself is not specifically Christian, nor merely a gesture. Ouspensky, in passing, covers this in The Meaning of Icons. The orans gesture was known both in Ancient Greek and Hebrew contexts before the iconographic types, as we know them today, had developed. In these contexts, as well as a few others, the orans gesture indicated not only a state of prayer, but the personification of prayer.

In this Mother of God Orans type, then, we have an established theology of the Theotokos being the personification of prayer. This reality is pushed even further by the liturgical use of this icon above the altar in Orthodox Churches. This means the Theotokos is not only the personification of prayer, but also the personification of the Church and the typological Ark of the Covenant.

More Spacious Than The Heavens

Our Lady of the Sign is often affectionately called Theotokos, More Spacious Than The Heavens. I personally prefer the latter because it more immediately communicates the theological thrust of the icon: The Uncontainable God contained Himself in the womb of the Virgin Mary, and thereby unites Himself to and redeems humanity. The former title gets us there as well, but first by calling to mind the prophetic word of Isaiah:

Therefore the Lord himself shall give you a sign; Behold, a virgin shall conceive, and bear a son, and shall call his name Immanuel. (Is. 7.14)

The miraculous virginal conception is the Sign announced by the prophet. The Incarnation, the revelation of the Second Person of the Trinity, and the knitting together of Christ’s human nature in His mother’s womb, are the major theological elements.

As we move through the major visual components of the icon of the Theotokos, More Spacious Than The Heavens, we’ll begin to see the profound relevance of this image to the Christian life. It’s my hope that this will also help us all move toward a more conscious and intentional veneration of the icon—the kind of veneration that results in communion.

The Mandorla

Although there are variations in which there are two mandorlas, one around Christ and the other around our Lady, for now we’ll only be considering the use of a single mandorla around Christ since that is the variation I used.

So…

…

…What the heck is a mandorla?

This Italian word describes the shape of an almond, and the shape is created by intersecting two circles. If you recall working on Venn Diagrams in grade school, the shape in the middle used for evaluating commonalities between two things is the mandorla shape.

We can also think of mandorlas existing on a spectrum. On one end are very strongly shaped mandorlas known as vesica piscis. On the other end are very softly shaped mandorlas that appear more ovular or circular. Regardless of the particular “strength” of any mandorla, the intersecting circles forming the mandorla can be understood as the intersection between two worlds.

Sometimes symbolic shapes and forms like the mandorla can provoke us to think about them in abstract and esoteric ways. But the use of these symbolic shapes is much more grounded and closer to home than we might expect. In the case of the mandorla specifically, it’s quite easy to perceive how the shape indicates a womb. Perhaps this became clear to you when I described some mandorla shapes, such as the one used in my own composition, as ovular. Oval means “egg-shaped”. A womb, then, is a powerful symbol not only indicating birth, but also the intersection between two worlds. The conceived child in the womb exists between the already and the not yet, between their creation and their birth, in the thin place.

The theology should begin to seem very apparent at this point, and we’re just getting started! Christ our God willed to be incarnate by the Holy Spirit and of the Ever-Virgin Mary. He condescended to be contained within the space between heaven and earth: the womb of the Theotokos.

You can see this theology demonstrated in my own composition. I designed the shapes and forms very simply. I also created complements and contrasts within that simple structure. Notice how Christ’s mandorla roughly follows the same kind of rounded shape used for the Virgin’s torso and shoulders. You could draw a third circle around her entire figure as well. The contrast to these shapes is the various linear cruciform patterns used throughout the composition.

Blue Light

St Paul’s encounter with Christ on the road to Damascus is a powerful story expressing apophatic theology.

Before encountering Christ, St Paul thought he saw everything clearly. He thought he had the right vision of reality, and that those Christian fools like St Stephen were the enemies of God. When the risen Lord appeared to him, and St Paul saw Jesus on the chariot-throne of Ezekiel, he was thrown from his horse and struck blind. Although he recovered some of his sight, it’s very likely St Paul was partially blind for the rest of his life. We know of a “thorn in the flesh” that hindered him in some manner, and that he wrote with large letters, and that most of his epistles were written by a companion.

The vision of Christ was so bright that St Paul’s physical eyes were darkened. This “darkness of God” that St Paul received acted to preserve him in a state of humility. Losing his sight granted him true sight. This is apophatic theology: knowing God by receiving unknowing through the revelation of Christ. Like pretty much everything in Orthodox spirituality, such as gaining life by losing life, this is a paradox.

A modern example would be a “blown out” photo. If you try taking a photo in an environment overly exposed to light, the camera sensor loses the ability to record information. The blue light of the mandorla expresses this. The light proceeding from the Unknown God is so bright that it appears to us as darkness, which is the deep blue at the center of the mandorla behind Christ. As the light moves toward us in concentric circles, the blue lightens. The light is the organizing principle allowing us to discern reality as much as we are able, and it is the “opposite” of how created light functions.

Take a look at a lightbulb (but please don’t stare into it—I need you to be able to read!). Notice that the brightness of the center of the light is almost completely white. As the light moves out from the center and into the world around it, the strength of the light diminishes and yet without failing the illuminate. The shadows are pushed into their proper places, and what do you know—you can see how you stubbed your toe! The uncreated light functions in the “reverse”: the center is dark but lightens as it moves outward.

I caveat the use of “opposite” and “reverse” because I think it’s better to think of the way uncreated light illuminates reality is the true way light and revelation functions.

Stare at the lightbulb long enough and you’ll go blind. Take one look at Christ with eyes “full of darkness” (Matt. 6.23) and you’ll go blind. The light which reveals the truth of the cosmos is also purgative, and this is why worldly people have a problem with Jesus. They prefer the darkness of human knowledge to the blinding light of divine revelation.

There are historic examples of using red instead of blue for the mandorla. The use of red forms a strong bridge between such icons and the Unconsumed Burning Bush icon. The divine fire illuminates the Theotokos without consuming or changing her (notice there are no purgative consequences for her), and this is another image of theosis or union with God. Although the bridge to the Burning Bush is stronger with the red mandorla, the theology is equivalent.

Three Stars

It’s typical to see the mandorla unadorned, but I’ve chosen to go with three stars in my own composition. The Festal icon for Theophany often includes a three-pronged beam of light in the composition, indicating the united operation of the Holy Trinity. This composition doesn’t allow room for something like that, which is why I’ve gone with the three stars. The Son eternally begotten of the Father is incarnate of the Holy Spirit and Ever-Virgin Mary.

I’m honestly not certain this was the best choice to communicate this, but I’m also not certain that even the three-pronged beam is much better. St Patrick’s shamrock and the Orthodox gesticulation for making the sign of the cross, along with the three-pronged beam, are all images that inadequately communicate the doctrine of the Trinity compared to the dogmatic expression of the Church. This is a bit of a rabbit-trail, but I bring it up simply to point out that both written and visual languages have their own limitations.

The Garments

The Theotokos is adorned in deep red and blue. The blue, which is mostly concealed, indicates the holiness of Theotokos. She is silent in her purity, adorned in three stars indicating her Ever-Virginity, allowing her holiness to be concealed by scarlet. Notice that the use of three stars mirrors the three stars of the Trinity. The communion of love shared in the Holy Trinity adorns the Theotokos.

The divine light of Christ radiates through her whole person such that the blue light of unknowing becomes a fitting garment. The theme of concealing and revealing is very subtle but important, and I’ll write on this another time.

Christ is adorned in gold and white. You can also see Christ adorned in white, and sometimes with gold as well, in the Festal icons for the Transfiguration and Anastasis. There is a theological bridge between these icons revealing that the Son of God is timeless and yet entered time.

The Gesticulations

As already mentioned, the Theotokos is posed with the orans gesture in her unceasing intercessions for us. Christ is blessing us with his right hand, while the other hand holds a scroll.

The scroll represents the judgment, and this is another theological bridge to the icon of the Transfiguration. The scroll contains the record of all humans deeds, and it remains sealed until the Final Judgment. Only Christ is worthy to break the seal of this scroll. Until the Day of the LORD, repentance and salvation is available to everyone. There is hope indicated, then, by scroll remaining closed. It means the contents can be changed if we repent in the body in the present.

Christ’s right hand of blessing emerges just beyond the veil of the mandorla, anticipating the full communion of Christ with humanity—in particular at the Eucharistic meal.

The Interpretation

The Heavens were too small for God, so He entered the womb of the Virgin.

The Theotokos is the Ark of the Covenant, the personification of the Church, of true prayer and union with God. The Uncontainable made Himself to be contained in her womb.

It’s wonderful to meditate on the holiness of our Lady, especially in contrast to our earlier consideration of St Paul. When St Paul encountered Christ there was a purgative consequence. His impurity was violently purged by the light of Christ. God willed to be incarnate within the Virgin, and the consequence was that her holiness was amplified. The presence of Christ in her made her pure and spotless womb more spacious than the heavens. How marvelous and awesome is this?! The heavens were too small for God, so He entered the womb of the Virgin.

The implication is that the Virgin Mary was already purified and holy before receiving the incarnate Christ in her womb by the Holy Spirit. There was no purgative consequence because there was nothing in her to purge. This state of purity is the ideal state of the humanity. It is also the ideal state of the fallen person before receiving Christ’s Body and Blood.

The bar is high, and the love of God is deep.

God choose to make Himself known to us, and He does this is the best and most beautiful way possible. He becomes incarnate. Not being circumscribable, God becomes circumscribed. Not being knowable, God makes Himself known. God deigns to make us participants of His holy, divine and immortal life-giving mysteries. He strengthens us in His holiness so that we might live according to His righteousness.

Baby Kicks, Again

…the third dimension of the icon is you…

Iconographers can suffer imposter syndrome just like anyone else. It often comes on very strong just before the finishing an icon. I felt imposter syndrome creeping up while working on the mandorla around Christ. It’s a bit lopsided due to the improvised and direct approach to painting I employed, which avoids using the tools that excite the passion of perfectionism (aka the compass).

I was feeling very bothered by the slightly lopsided mandorla and had been considering repainting it. But then I was listening to Michael Garten and heard him talking about the three-dimensionality of the icon…

I suddenly remembered all the times when Yam held my hand on her womb to feel our children kicking and moving about. I also suddenly remembered that there were occasions when I could briefly see their movements. Sometimes the pushing against the proverbial veil was so strong that the round shape of Yam’s womb would go lopsided for just a brief moment. It was the breath of another universe was moving into my own.

I’m gonna go out on a limb and say that the lopsided mandorla was a happy accident. My human imperfection, my weakness, became a touchpoint for a more profound perception of the three-dimensionality of the icon.

If you haven’t picked up on it already, the third dimension of the icon is you. Every element comes together for the purpose of drawing you into the composition to experience communion with our God and Savior Jesus Christ and His Mother.

But there is a veil (the iconostasis).

We cannot know God without being purified and illumined, and this process can sometimes be very difficult while at once being a joy beyond sorrow. But if we can at least try to become like the Theotokos and conceive Christ in our hearts, then it’s possible that our own bodies can become thin places. We can become meeting places between heaven and earth for all the people we love, and even our enemies. By God’s grace, our hearts will become more spacious than the heavens.